‘How should one read a book?'

Woolf (roughly) on this day, 1925.

It is early November in Tavistock Square, London. Virginia is still writing in recovery mode, and there are times in this letter where she seems to struggle to be her usual, glittering self. There are a few half-baked sentences and one moment where the perfect image slips out of her grasp. It will be another month before she’s any stronger.

Vita remained the object of Virginia’s affections and so it is only fitting that today’s ‘Woolf on this Day’ post should be a letter to her. As in the note from October 13th where Virginia rebuked Vita for moving to Persia, Virginia occasionally adopts teasing, wounded tones. She begins assertively, but then later imagines herself as Vita’s humble lap dog, a fawning creature who’s liable to get her nose rapped when she steps out of line. Power-play, flirting, and the swapping of general news mingle in this glimpse into Bloomsbury during the winter of 1925.

Wednesday [early Nov], 1925

Tavistock Sq, London.

My dear Vita

This is the only paper I can find. I cannot remember where we had got to: cruelty? I was cruel, you said. I say, no, not cruel, only being ten years (I suppose – b. 1882) older than you, thus in another climate altogether, honesty was so important that all my spies had to be forever watching what came in with a view to imposters. I will explain one day.

I am alone, too. Leonard speaking at a meeting, then going to a party, where a poor widow, whose husband died by inches, throughout his youth, of paralysis, is trying to fan a sort of ghostly flame alive again.

She tells me awful things – but no matter: Don’t lets go into death and disillusionment. Aren’t you one of the nicest and magnanimous of women? I think so. “Esteem” is a damned cold word – (yours for me) Still I accept it, like the humble spaniel I am.

We then come to what? – Not much news here. I wish you were in the chair opposite. Yes, I am actually sitting up, after dinner; and no pain.

Yes, I am very fond of you: but the poor spaniel will have its nose rapped if it says anything more.

I have to write a lecture, for school girls: “how should one read a Book?” and this, by a merciful dispensation, seems to me a matter of dazzling importance and breathless excitement.

But I have been trying to prove to Raymond Mortimer that this is not vanity; No; I am not much impressed by what I do; only intoxicated by what is something like your night, your solitude, in which, as I maintain we writers – oh but I cannot find the image. So come and catch it. Its a question of being alone, in writing.

Yr VW1

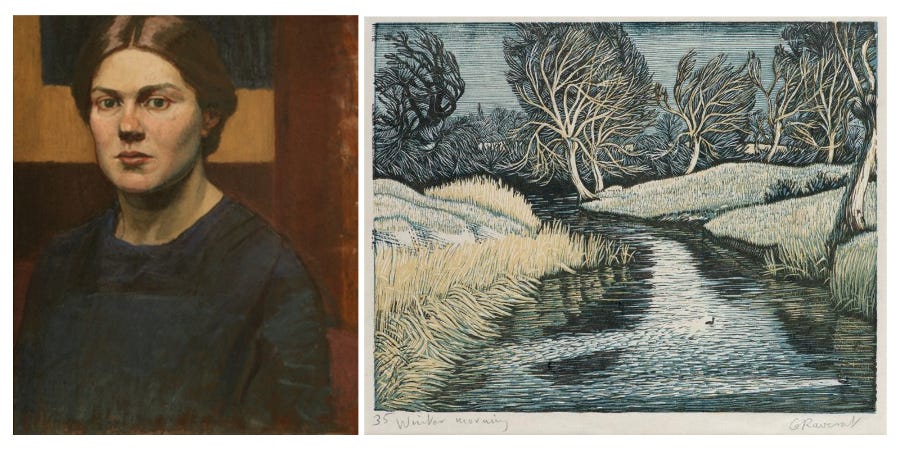

The ‘poor widow’ in this letter is Gwen Raverat, the brilliant Cambridge-based artist who had just lost her husband, Jacques, to multiple sclerosis. Gwen was the granddaughter of Charles Darwin, the first cousin of the poet Frances Cornford, the second cousin of Ralph Vaughn Williams, and was related to the prominent Wedgewood family. Gwen showed every sign of living up to her family’s reputation for success, studying at the Slade School of art and becoming an accomplished wood engraver and painter. Gwen and Virginia’s paths intersected at various points in their early years and they fell into the same bohemian circles as adults. Both were influenced by Rupert Brooke’s neo-paganism and they each found solace in the vibrant community of the Bloomsbury group. Gwen’s husband, Jacques, was also an artist and a close friend of Virginia’s. There were so many letters between Virginia and the Raverats that they have since been published as a book.2

It’s hard to recognise Gwen in the figure of a desperate woman trying to fan the ‘ghostly flame’ of her youth, but it is worth remembering how much had changed in recent years. 1925 seems early in Virginia Woolf’s career, but the Bloomsbury of fifteen years ago had already dissolved. Thoby Stephen, Katherine Mansfield, and Rupert Brooke were all dead, and Jacques had joined them. Those that remained were left to wonder if their best years had been lost.

Virginia’s essay ‘How Should One Read a Book’ was written as a talk for a girl’s school in Kent.3 It takes a sensitive, quizzical approach to the problem at hand, feeling through the many difficulties facing the reader-in-training. Just as in A Room of One’s Own, the impediments stand out more than the solutions, and the solutions are more or less common sense, but the journey is still inspiring and vividly rendered. One of her best pieces of advice is to think more like a writer than a reader:

To read a book well, one should read it as if one were writing it. Begin not by sitting on the bench among the judges but by standing in the dock with the criminal. Be his fellow worker, become his accomplice. Even, if you wish merely to read books, begin by writing them.4

It is hard to imagine Raymond Mortimer viewing Virginia’s talk as anything less than altruistic, but his allegations of vanity hardly ruffle her feathers.5 It helps that she’s clearly distracted by what she calls Vita’s ‘night,’ her ‘solitude.’ As she focuses back on her favourite subject you can see her images build and coil, layering a theory of writing onto the sensuous image of a solitary Vita – but she falters, stumbling to a halt. It’s ‘a question of being alone, in writing,’ she adds, before returning to her own solitude.

VW - VSW Wednesday in early November, 1925. All errors Woolf’s own.

They were published by William Prior (Gwen and Jacques’s grandson) as Virginia Woolf and the Raverats (2004).

The resulting essay came out in the Yale Review in 1926 and was then included in the second Common Reader series.

‘How Should one Read a Book?’ (1926)

Raymond was a writer, critic, and a close friend of Vita Sackville West.

Thank you for this, Karina - it’s just wonderful!

How many of you thought about Flush, while reading Virginia's words?

Thank you for this post